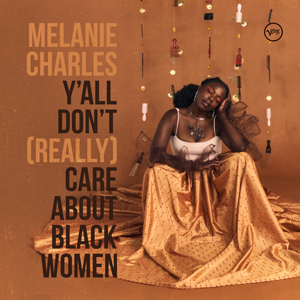

MELANIE CHARLES

There are very few artists whose sound can capture the sentiments of a generation. The Brooklyn born and raised, Melanie Charles, is one of these artists. Over the past few decades, she has made a name for herself through dynamic engagements with jazz, soul and R&B. Her bold genre-bending style has been embraced by a range of artists including Wynton Marsalis, SZA, Mach-Hommy, Gorillaz and The Roots. In 2021, she appeared on NPR’s Tiny Desk and stunned with her eclectic style. Through it all, she has remained committed to making music that pushes listeners to consider new possibilities—both sonically and politically. “Make Jazz Trill Again,” a project that she launched in 2016, demonstrates her allegiance to everyday people, especially the youth and is focused on taking jazz from the museum to the streets. “I love jazz, I really fell in love with it deeply. But I was interested in young people interacting with it,” Charles says. The album Y’all Don’t (Really) Care About Black Women is reflective of Charles’ tremendous versatility and imagination as an artist but of also her deep care for community.

Y’all Don’t (Really) Care

About Black Women

Charles’ initial approach to the album was simple—to find music in the Verve catalogue that spoke to her. As a Verve remix project, with Y’all Don’t (Really) Care About Black Women she set out to take this group of songs and breathe new energy into them. She was immediately drawn to the rapturous voices of Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughn who inspired her to record arrangements of “God Bless the Child” and “Detour Ahead.” By the time she was ready to move forward with recording the rest of the album, the world had transformed into a very different place. When the pandemic hit, Charles was faced with a new set of concerns. She no longer had access to the same resources and was forced to make the album from home. Charles was not discouraged. “This is at the center of our experience as brown and Black people, making something out of nothing,” she says.

The remainder of the album was recorded during the summer of 2020 while the pandemic continued and Americans were in the throes of a racial reckoning sparked by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others. Taylor’s death, in particular, had an impact on Charles’ creative process. “I was rudely reminded that Black women are and always have been undervalued, uncared for, unprotected and neglected. I decided to focus on songs written and or sung by the Black women who paved the way for me,” says Charles. Y’all Don’t (Really) Care About Black Women is a love letter to the unheralded labor of Black women. At the same time, it asks listeners, as they consume the artistic production of Black women—the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Abbey Lincoln and Dinah Washington and others—to be accountable to and care about them as well.

Although Charles may be new to some, she has held a long spanning relationship with music that goes back to girlhood. She was raised by a Haitian mother in Brooklyn where the sound waves in their home was filled with artists like Johnny Hodges, Frank Sinatra, Chaka Khan, Anita Baker, John Coltrane and Nat King Cole.She attended the famed arts high school, LaGuardia High School for the Performing Arts where she studied flute and vocals. Her early life was full of stage performances; as a kid she participated in musical theater, pageants and talent shows in New York City. Eventually, she landed at the School of Jazz and Contemporary Music at The New School for college where she met artists like singer, songwriter, and record producer Jesse Boykins III and alto saxophonist Lakecia Benjamin. Perhaps better known as a singer, Charles has earned her title as a bonafide flautist. Her playing adds vibrant swaths of color and emotional texture to her music.

The album opens with a breathtaking rendition of Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child.” This song, and the album overall, flexes Charles’ impressive arrangement skills. The song features a powerful group of musicians—Benjamin Julia on electric guitar, Dezron Douglas on upright bass, Anwar Marshall on drums, Shedrick Mitchell on organ, and Tayzaro on cello. On flute and vocals, Charles floats above the soulful current of the band, singing the song over a dramatic blanket of electronic sound. The lyrics ring with equal power as the music. When Charles sings the lines “Yes, the strong get more/ While the weak one’s fade,” the connection to Black women’s struggle is palpable. “My experience moving in the world as a Black girl has always been, I have to be strong. I have to keep it together; I have to sort of live up to the standard,” says Charles.

At its core, Y’all Don’t (Really) Care About Black Women is a clarion call for a more intersectional vision of the world in which Black women can live more freely and express their full humanity. The interlude “Pay Black Women” offers the most explicit instruction on some of the ways that care can be expressed. It contains a sample from a film project produced by Charles in 2021 entitled Love Letter to Black Jazz Girls. Through the voices of three Black women, the track draws attention to the racial gender wage gap but also to the treatment of Black women artistic producers more broadly.

“Go Away Little Boy” is an inventive interpretation of a tune that was originally recorded by soul singer, Marlena Shaw in the late1960s. Charles transforms the whimsy of the Shaw’s version into a slow and sensuous 90s R&B groove. The song touches on some of the more intimate dimensions of Black womanhood—romantic longing, desire, and difficult love. Likewise, in “Perdido” Charles sings about lost love with Dinah Washington’s voice deftly sampled throughout. Washington’s voice trails through the tune as Charles leads us through a bright, beat-clapping twist on the jazz standard.

In this fresh compilation, Charles leaves listeners with a powerful statement on what solidarity with Black women can look like. It includes not only care and attention to the everyday struggles that animate Black women’s lives but also to the beauty and joy as well. The album closes with her interpretation of “Beginning to See the Light” originally sung by Ella Fitzgerald. In this final provocation, Charles transforms Fitzgerald’s laid back swing into a hip-popping jaunt. “I just see people twerking to [it],” says Charles.

For more information, please contact Louis D'Adamio

or Carla Sacks at Sacks & Co., 212.741.1000.